Career milestone: Postdoctoral fellow Martin Munz to lead early cortical circuits research as a professor in Canada

“I want to understand how the brain is built,” says Martin Munz, a post-doctoral scientist in the laboratory of Botond Roska at IOB. Munz and his colleagues investigate the assembly of circuits in the cortex–which is the part of the brain that governs sensory perception, cognition, and other higher-order functions. His proposal to study the effects of autism-relevant mutations on cortical development in mice was recently awarded three years of fellowship support by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI). The SFARI fellowship is designed for early-career scientists transitioning to independent faculty positions. Munz will now be moving to the University of Alberta, Canada, for a job as assistant professor in the Department of Physiology.

Munz’ research is grounded in his fascination with the biology that drives natural behavior. He recalls that as a young child growing up in southern Germany, he was more interested in learning about the animal species portrayed in children’s books than in hearing the stories about them. He finished his undergraduate studies in applied biology in 2007, and then went to the Charité, a university hospital in Berlin, for a Master’s Degree in medical neuroscience. Working with his advisor, Michael Brecht, Munz studied the hunting behavior of the Estruscan shrew, a tiny mammal that needs to consume nearly twice its own body weight in food every day. “Otherwise, it dies,” Munz says. “And what we in the Brecht lab wanted to know is how this insect prey capture behavior encoded in the shrew’s brain?”

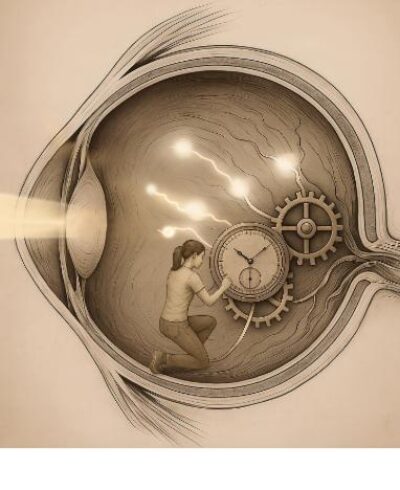

Munz was intrigued by neuroscience, especially by how the environment itself rewires growing brain circuits. During his Ph.D at the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University, Munz studied how the firing of retinal cell axons shapes growth and connectivity in the developing visual system, and developed an approach for observing axonal branching in tadpoles at high temporal resolution. But he also wanted to explore how cortical circuits form in mammalian brains, inspired in part by research showing that axons growing from the thalamus towards the cortex pause at certain points of development. This waiting period made sense, Munz says, given that brains aren’t built all at once. “There has to be some sort of temporal structure,” he explains. “If you’re building a house, you can’t start with the roof first and then the walls. Things have to go in a certain order.”

After finishing his Ph.D., Munz reached out to Roska to inquire about post-doctoral opportunities. Roska was then based in the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, in Basel, and he was interested in Munz’ plan to probe the effects of neuronal activity on cortical connections. “He said, ‘Let’s do this,'” Munz recalls. “And once you step in to Botond’s lab, you can see that the sky is the limit in terms of any experiment you want to do.”

Munz joined Roska’s lab in 2015, and was soon accompanied by another post-doc, Arjun Bharioke, as they shared many research interests. From then on, Munz and Bharioke worked closely as a team; using modern genetic tools to target and record the activity of different cell types across the cortex. The mammalian cortex is organized into six layers with distinct neuronal cell types, and each layer has unique roles in circuit functioning. Munz and Bharioke focused especially on layer five pyramidal neurons, which develop very early in the embryo and serve as a major cortical output both across the cortex and to different brain areas. Newly available transgenic mouse strains were essential for the research. The animals had engineered neurons that fluoresce brightly when active, enabling the scientists to observe how different cortical layers interact. Munz and Bharioke anesthetized the animals during their experiments, and that prompted a question: How do general anesthetics change cortical activity during periods of unconsciousness?

The pair set out to investigate. And their findings showed that while different anesthetics have varying neuronal activity patterns, the drugs all converge on layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the same way. While the animals are conscious, the layer 5 information output is high. But in the anesthetized state, layer 5 neurons have very low information output. To illustrate the point, Munz draws an analogy with football fans in a stadium. Before a game, football fans chatter amongst themselves (total information high). Then after the game is underway, the fans all shout together in a synchronized way (total information low). Similarly, the activities of layer 5 neurons synchronize together in anesthetized mice, such that the cortex becomes disconnected from the rest of the brain.

A year later, Munz and Bharioke published a second paper observing the inception of cortex in the living mouse embryo. The prevailing view had been that pyramidal neurons become active only after reaching their final locations in the cortex. But the two scientists discovered something new about this process: layer 5 contains an early transient circuit that is already active even before the six-layer cortex fully develops. That circuit, they found, contains two layers, one being a “superficial” layer that ordinarily disappears as the animal grows. In an engineered mouse model of autism, however, the superficial layer lingered as an active developmental remnant. The findings suggest this newly-found transient circuit regulates how pyramidal neurons are spatially organized, and that changes affecting it may contribute to neurodevelopmental problems, including autism.

Importantly, Munz and Bharioke made this discovery only after devising a way to stabilize live embryos for research. Pyramidal neurons are so small that any movement can easily lead to faulty activity readings. To control the embryos for single-cell neuronal imaging, the scientists came up with a way to secure the embryos in agar-filled holding devices within the mother’s abdominal cavity. “That way we can keep the embryos close to where they normally reside near the placenta, and keep them stable that way,” Munz says.

Describing himself as a developmental neurobiologist, Munz says he intends to continue investigating how brain cells connect and communicate with each other to make cortical circuits. He’s particularly interested in the effects of neural activity on the brain’s organization. “How does embryonic development lead to a functional brain in adults?” he asks. Autism also figures prominently in Munz’ research plans. He points out that certain genes when mutated confer high risks for the disorder. “And what I want to know is how those genes impact on development and functioning,” Munz says. “The basic idea is to understand step-by-step how a circuit forms and then interfere with genes that are known to be associated with developmental disorders. Then we can ask, ‘At what point do things go wrong?’ And we look at this development from the very beginning–when the circuits are just forming.”

Recent News